The American Buffalo: A Story of Resilience

Special | 56m 35sVideo has Closed Captions

Judy Woodruff moderates a conversation with filmmaker Ken Burns and three experts.

Judy Woodruff moderates a one-hour conversation with filmmaker Ken Burns and three experts: Jason Baldes, Rosalyn LaPier, and Dan Flores. The discussion explores lessons from the film - the early history and special relationship between native American people and the buffalo; its relation to the larger grassland and prairie ecosystems; and Tribal contributions to restoration of the buffalo today.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate funding for The American Buffalo was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and its...

The American Buffalo: A Story of Resilience

Special | 56m 35sVideo has Closed Captions

Judy Woodruff moderates a one-hour conversation with filmmaker Ken Burns and three experts: Jason Baldes, Rosalyn LaPier, and Dan Flores. The discussion explores lessons from the film - the early history and special relationship between native American people and the buffalo; its relation to the larger grassland and prairie ecosystems; and Tribal contributions to restoration of the buffalo today.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The American Buffalo

The American Buffalo is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipFUNDING: The Better Angels Society is proud to support this presentation of "The American Buffalo: A Story of Resilience," part of the "Ken Burns Public Dialogue Initiative at Georgetown University."

DeGIOIA: Hello.

My name is Jack DeGioia, President of Georgetown University, and I'm pleased to welcome you to this discussion about "The American Buffalo", a new film directed by Ken Burns.

Georgetown has been honored to work with Ken to encourage open civil dialogue through the exploration of history.

In a few moments, Judy Woodruff will lead a conversation with Ken and a group of experts, Rosalyn LaPier, Jason Baldes, and Dan Flores about the history of this magnificent species, its importance to North American ecosystems, and its special relationship with Indigenous people over the last 10,000 plus years.

We hope you enjoy this special discussion.

ANNOUNCE: Now here's the moderator for "The American Buffalo: A Story of Resilience" from the "PBS NewsHour", Judy Woodruff.

WOODRUFF: Hello and welcome to this PBS special program, "The American Buffalo: A Story of Resilience" to preview Ken Burns' new film on the extraordinary history and legacy of the largest land animal of the western hemisphere.

Over the next hour, we will take a closer look at the buffalo, also known as bison, who have been on this continent for more than 10,000 years.

How did this magnificent animal contribute to the creation of this country?

How did their numbers drop from the tens of millions to fewer than 1,000 in less than a century, edging them close to extinction?

And what efforts are being made to preserve and restore the population in a lasting and integrated way?

To have this conversation, I'm delighted to be joined by the renowned filmmaker himself, Ken Burns along with Rosalyn LaPier.

An indigenous writer, and ethnobotanist, and a Professor of History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; by Professor Emeritus of Western History at the University of Montana, Dan Flores who is the author of, "Wild New World: The Epic Story of Animals and People in America" and by Jason Baldes, Tribal Buffalo Program Manager for the National Wildlife Federation's Tribal Partnerships Program.

Welcome to you all!

Let's begin with a look at a clip from this 4-hour film, "The American Buffalo," it's an excerpt which lays out the extraordinary ecological impact of the animal as well as their close co-evolution alongside Native Americans.

RINELLA: If you see one out grazing, it looks so, "slow."

It's like a parked car sitting there.

But they can clear six-foot fences.

They can jump, a horizontal jump, of seven feet.

They can hit a speed, hit the speed of 35 miles an hour.

And you're talking about something that can get going that speed that's 1,800 pounds.

It's like a souped-up hotrod of an animal hiding in a minivan shell.

NARRATOR: Fully grown, an American buffalo can weigh more than a ton; stand taller than six feet at the shoulder; and stretch more than ten feet long, not including the tail.

Huge as they are, they are small compared to some of the prehistoric animals that once roamed the continent: woolly mammoths, giant ground sloths and camels, and other species of bison, one of which had horns that sp anned 9 feet from tip to tip.

After humans arrived in North America more than 20,000 years ago, all of the biggest animals, along with nearly 50 other species, went extinct on the continent, from either hunting, or changing climate, or a combination of the two.

In their place, the modern buffalo evolved and multiplied, particularly on the gr asslands of the Great Plains.

FLORES: Bison and humans, in, in a real sense, co-evolved alongside one another over the last 10,000 years, or so.

Sometimes the animals would ebb and flow.

But they always rebounded.

And, so, there was this wonderful kind of dynamic equilibrium that lasted for more than 10,000 years.

LaPIER: They have always lived with humans.

They've always been hunted by humans; they've always had predators, so their entire sort of evolution as, as an animal species has been as an animal that has been, um, hunted.

PUNKE: And their primary defense mechanism is to, to run away.

And they have that skill at a very young age.

A newborn buffalo calf tries to stand, for the first time, at the age of two minutes.

And, at seven minutes, they're able to run with the herd.

NARRATOR Over the centuries, their grazing habits on the wide expanses of the Great Plains proved crucial to its ecology...

The types of grasses that flourished there, and the other species that thrived alongside the buffalo.

Even when they stopped and sometimes dug through the grass with their horns, and then rolled in the dust, creating "buffalo wallows", the bison's habits helped support other forms of life on the Plains.

LaPIER: It's not just one wallow; we're talking about millions of bison, which means millions of wallows.

DANT: those wallows could do a couple of things.

At its most simple and basic, it's a "dirt bath."

But then, it also has an ecosystem function.

Water retention.

If it rained, these become shallow little ponds and pools.

And that, in turn, affected the landscape, as well.

LaPIER: Because it's also a disturbed area, plants that flourish in disturbed areas will also, then, grow around a wallow.

So, they became these really great areas, not only for, um, wildlife to use, but also for humans to use because of the plants that were there.

WHITE: When the buffalo are here, the land is good.

When the land is good, the buffalo are healthy.

We have lived here for 600 generations.

We have been here, conservatively, 12,000 years.

So, if you think about that 12,000 years, imagine that on a timeline.

And then, take that 12,000 years and wrap that timeline around a 24-hour clock.

What that means is that Columbus arrived at about 11:28 PM, and Lewis and Clark, at about fifteen minutes before midnight.

WOODRUFF: Just a remarkable clip from the film.

And Roslyn, I want to begin with you.

And we should add, you're a member of the Blackfeet Metis Tribe.

And what we heard you speaking about and the others in the film is how the buffalo evolved with humans.

Even at the same time, it was being hunted by humans.

Explain how that could be.

LaPIER: Well, one of the things we know about bison, of course, the modern bison that we know today, they evolved here in North America, and they evolved at the same time that Indigenous people had already been here for probably 10,000 years.

And so Indigenous people and the bison sort of lived together in the same places, in the same areas.

And because the Indigenous People hunted bison, bison just grew along a lot of different Indigenous Nations and became the sort of, animal of choice, both for not just hunting to eat, but also to use for a lot of the materials that they used for daily life, but then also gave them a lot of meaning.

You know, bison became very much enmeshed in Indigenous Religion and religious practice, and that was because of this long, you know, thousands of years a relationship that was developed across the Great Plains during this first sort of 10,000 years of their history.

WOODRUFF: And Dan Flores, I mean, it is one of the, I think, most remarkable things that most people are not aware of.

And that is, as we just heard from Roslyn, how long this relationship goes back, how long the buffalo were here.

It's almost impossible to comprehend.

Give us a sense of-of how that length of time allowed this co-existence to take place.

FLORES: Well, if you think of those 10,000 years that Roslyn just referred to as an inhabitation of North America, that compares roughly to that of the United States.

United States has been here a little more than 300 years.

So, we're talking about a depth of time that's 30 or 40 times longer than just the existence of the country that we all think of as being fairly old now and being three centuries old.

So, it's a very old relationship.

Bison and humans not only co-evolved, but bison really pretty much adapted to the presence of humans during their emergence 8,000, 9,000 10,000 years ago and to their modern form.

I mean, they became smaller, they had a quicker reproductive turnover and they and their habits and their range, they were really kind of regulated to some degree by native people.

It's the oldest and this is an easy way to think of it.

It's the oldest economic life way, this relationship between humans and buffalo, and particularly hunting buffalo on the part of humans.

It's the oldest economic life way in North America.

We don't have anything else that compares to an 8,000 or 9,000 or 10,000-year way of life for humans on this continent.

WOODRUFF: And Jason, we don't we don't think of this as a, an economic relationship typically.

But that's it's very much what it was.

BALDES: That's exactly right for the Eastern Shoshone people.

We were even went so far as distinguishing ourselves by the foods we ate and the Eastern band, the Shoshone, we called ourselves the "Guchundeka", the "Buffalo Eaters".

And even though this animal's been missing or was missing for 131 years, it's still in our DNA.

It's in our songs.

It's in our ceremonies.

It's actually critical in our ceremonies.

And nutritionally, you know, that that animal's critical, as critical today as it was for our people then.

So, it's intricately intertwined into who we are.

WOODRUFF: And Ken, what drove you to this?

What compelled you to want to look at the American buffalo?

BURNS: Well, I think, Judy, the big thing is, is that it's so intertwined with the history of us in all of the intimacy of that word and all the bigness of the United States.

And it's humbling.

We-we have to sort of take a step back and understand that we're studying not just the story of this animal, which is a fascinating and ultimately positive story parable of de-extinction.

But it's a tragedy going in as we watch their numbers go from 30, 40, 50 million on the Great Plains to fewer than not just 1,000, maybe even fewer than 100, wild and free and, and that story is a story of Native people, all the different nations, Indigenous tribes that were interrelating with the buffalo in the Great Plains.

So, I think in some ways our delay in getting to it permitted us to become a little bit smarter, but also a little bit more, gather a little bit more humility, and begin to understand this story differently from the way we tell it.

I mean, the buffalo is, you know, from, as we like to say, from the tail to the snort used by so many of the different tribes completely.

It's just an amazing story that touches on nearly every aspect of our complicated history.

WOODRUFF: And that's what comes through so clearly in this film.

Roslyn, why do you think the Native American part of this story has not really come out before now?

LaPIER: That's a great question, Judy.

And I think it's there's a lot of different answers to that.

I think that one, I think that we're just learning so much more now today from Indigenous peoples themselves about sort of the traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous knowledge that Indigenous people hold and then kind of integrating that with what we learn from kind of Western science and academia.

And I think that that helps tell a much more holistic story about the bison.

And I think that now of course today there's a lot more folks like myself, you know, who are people who are raised with indigenous knowledge but now also have academic training.

And so, we are able to blend those worlds and be able to tell kind of this larger story of the bison here in native North America.

And I think one of the things that is an important point to make at the beginning is, oftentimes Indigenous people, because we had this long history with bison, we really understood bison.

You know, through again, thousands of years of observation and-and living with bison, that kind of that common misnomer stereotype that we often hear that you know, Indigenous people like followed the bison.

Indigenous people probably rarely followed the bison.

They created landscapes, they managed the land in ways that bison would come to them, and that they knew where to go, to go look for bison.

WOODRUFF: And Dan, what's your sense of why it's taken so long to get this critical part of this story to the forefront, to be told so that people can understand it in a way we've really never understood it before?

FLORES: Well, I would say, Judy, that one of the issues has been that it's only been in the last century, really since the 1920s.

So, 100 years ago that we understood that Native people had been here for many, many thousands of years.

I mean, in the early 1920s, even people that anthropologist at the Smithsonian were arguing that Indigenous people had only been in North America for a couple of thousand years before Europeans arrived.

But we discovered in-in Folsom, New Mexico, a site, an archeological site that was, came to light as a result of an African American cowboy locating the bones of very large, clearly extinct versions of bison.

And a few years later, archeologists realizing that there were actually flint tools buried in the vertebrate of those animals of-of those remains, that North America had a really old history.

We had sort of thought even 100 years ago that North America really started when Europeans arrived.

And suddenly now, only 100 years ago, we began to realize that this history stretches back into the dimness of time.

And so over that past hundred years, we've gradually been putting together this story...

So, we're all kind of excited, I think, to be able to bring this deep-time story to a modern audience with all the nuances that we've been able to add to it here over the last 20 or so years as a result of breakthroughs in scientific knowledge and finally beginning to talk to Native people and asking them what they know themselves.

WOODRUFF: And Jason, when you think about the Europeans coming on the scene and things changing so quickly, it was almost breathtaking how quickly things turned, wasn't it?

BALDES: It really was.

And we have to consider the eras of federal Indian law and policy that were really were to dismantle the ways of life of Native people.

These six or seven eras, you know, are the reservation era of termination relocation.

You know, during the civil rights era, we kind of have self-determination really, where we have a, you know, the upholding of-of sovereignty and self-determination.

So, you know, those eras were pretty preventative of-of tribes exercising things like buffalo restoration.

So, we're in a new era now and, you know, the recognition of this history, but also the federal government's role in that and the trust responsibility that the government has now to assist our tribes in restoring buffalo.

And, you know, we now have 83 member tribes of the Intertribal Buffalo Council.

There's folks like the National Wildlife Federation, you know, upholding and assisting in restoration.

There's cultural, academic, nutritional, ecological reasons for bringing the species back.

And so, I think we're in a new era in buffalo are foundational to that.

WOODRUFF: And Ken, going back to your really the first part of this film, the first hour, where you so clearly establish what happened when the Europeans came on the scene, it-it happened so quickly over the span of time and completely changed the-the presence of the buffalo on the American continent.

BURNS: So, Dan talked about the economic relationship, the oldest one, the new economies of hides.

And then later bones are going to conspire in a kind of God-awful way.

There's no other way to put it.

This unbelievable tragedy of the slaughter of the buffalo all up and down the plains from the southern to the central to the northern plains.

And it is a story that we kind of have to be reminded we have to look at.

We have to own the story.

And we also have to begin to see that our relationship to things is not the only relationship to things.

And when I say our I mean the European and-and-and White American version of things.

WOODRUFF: And when, as you say, when it comes to the buffalo, the destruction that we're talking about occurred over just a matter of a few decades.

And that's what we are confronted with in this film.

In this next clip from the film, where we see the extent of what is called the "final" slaughter of buffalo and the economic impetus behind it.

It was 1881, a year when the market surged for buffalo hide and for expanding railroads, as hunters and their big guns kept moving west, across the great plains and into the Rocky Mountains.

NARRATOR: That same year, the Northern Pacific reached Miles City in Montana Territory.

Soon, 5,000 hide hunters and skinners were spilling over the plains, from the Yellowstone River to the Upper Missouri, where they set up what one army lieutenant called "a cordon of camps...

Blocking the great ranges and rendering it impossible for scarcely a single bison to escape."

The killing commenced, all over again.

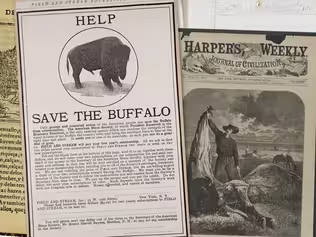

Meanwhile, in New York, 31-year-old George Bird Grinnell had become editor of "Forest and Stream", a publication for hunters and fishermen that he was prodding to take on issues of co nservation with more urgency.

During the hide-hunting on the southern Plains, he had advocated for policies he called "just" and "honest" toward Native Americans that would, he wrote, "conscientiously aid in the increase of the buffalo, instead of furthering its fo olish and reckless slaughter."

Now, Grinnell turned his attention to what was unfolding in Montana.

GRINNELL: Up to within a few years ago, the valley of the Yellowstone River has been a magnificent hunting ground...

The progress of the Northern Pacific Railroad, however, has changed all this.

The buffalo will disappear unless steps are taken to protect it there.

PUNKE: This is the era of the myth of inexhaustibility.

The belief that the West is so vast, that the resources are so vast, that they can never be exhausted.

But it was so much in front of them what was happening that I think they began to figure it out.

It became more and more difficult to find buffalo.

And there were ominous signs.

Weird things began to happen.

Like, they would find herds that were comprised entirely of calves.

But there also was a capacity to deny and to believe that they had just gone over the next ridge line.

Gone into the next territory.

And, so, all of that kind of mixes together.

NARRATOR In Miles City, in the fall of 1883, the hide hunters prepared for another winter on the Plains, believing there must still be plenty of buffalo between the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers.

They came back in the spring, with almost nothing to show for their efforts.

RINELLA: There are people in Miles City who had been hide hunters and they're simply lolling around waiting for the return of the herds.

They still thought there has to be some, somewhere.

When they had finished, they didn't know they'd finished.

They felt that, well, it can't be over.

And it was over.

NARRATOR: In 1884, the total number of hides brought to the Northern Pacific fit in a single boxcar.

MAYER: One by one, we runners put up our buffalo rifles, sold them, gave them away, or kept them for other hunting, and left the ranges.

And there settled over them a vast quiet...

The buffalo was gone.

Frank Mayer.

FLORES: There is no, no story anywhere in world history that involves as large a destruction of wild animals as happened in North America in the Western United States, in particular, between 1800 and about 1890.

I mean, it is the largest destruction of animal life discoverable in modern world history.

LaPIER: Why Americans are so destructive; I think is an important question to ask.

Why is that part of our story?

Why is that part of our history?

WOODRUFF: And to you, Roslyn, that is such a sobering statement, America.

And how destructive have Americans been?

Do you have an answer to that?

LaPIER: You know, I'm not sure if I do have an answer to that, although I do want to sort of make a clarification in that this this is an American story.

I think we often when we think about the past and we talk about the heritage of the United States of America, we often talk about Europeans and European heritage.

And by the time we're talking about the 19th century, we really are talking about the United States of America and Americans.

And it really is Americans who are complicit in this destruction, again, not just of bison, but of a lot of the different animal species and even plant species on the northern Great Plains or on the Great Plains.

So I think it's one of the things that other people have brought up of we-we see what had happened in the past and that maybe this is a time for us to really rethink ourselves as a country, as the United States of America, our own complicit part of this tale of destruction, and perhaps how then today we can restore and-and redevelop and revitalize the relationships between bison and Indigenous people, but also bison and Americans.

WOODRUFF: I do want to come back to this question that, Dan, that that Roslyn raises in the film, and that is why Americans are so destructive.

She was referring to that particular period of the 19th century, but others have-have broadened it out to the scope of American life.

How do you see it?

FLORES: I see it as a, the bison story is part of a bigger context, I suppose, Native people saw themselves as being kin to other animals.

I mean, they, in effect, presaged the Charles Darwin idea from the late 1850s.

And that of course became the substance of the whole ecology, the science of ecology and the ecology movement in the 20th and 21st centuries.

But Europeans old worlder's brought with them notions of-of human exceptionalism, a religious tradition that humans were different from every other life form on the planet.

We were the only ones made in the image of a deity, the only ones with souls.

Other animals lacked those kinds of connections.

And we also, of course, brought with us the idea of the Adam Smith global market economy and John Stuart Mills ideas of freedom.

And so those all combined into a kind of approach to North America where we decide we're going to emulate the old world in its destruction of its own charismatic animals.

And we're going to do the same in North America in the name of civilization and in the name of making the United States a rich and leading world power.

And we do so essentially by turning North America into a congress of market resources, and that includes beavers, fur seals, sea otters, passenger pigeons, great orcs.

I mean, the list goes on and on and on.

And of course, it includes bison as well.

I mean, to me, one of the striking sort of summations of this is the passenger pigeon story.

Those birds had been in North America for 15 million years.

They could not survive 400 years of our presence here.

And bison, which had been here for at least 150,000 and perhaps 300,000 years were in the same situation between 1800 and basically the 1890s.

We managed to shrink them from at least 30 million animals down to, as Ken mentioned, just a few score that were left, so few that conservationists worried whether there was enough genetic variability to really be able to save them for the future.

So, it's a, it's a story that I think we've never really confronted.

WOODRUFF: And Jason, how do you come at this question of why this destructive force on the part of Americans?

BALDES: I think it's a notion of exploitation.

As others have mentioned, this-this country was-was founded.

And then what we've done is plow up, pave over, fence in-fence out, you know, one of the get on airplanes and fly east.

And you look down and all you see is-is checkerboard and agriculture.

So, the-the idea of exploitation or being able to extract resources or, you know, provide, you know, put livestock on the ground to-to raise for your livelihood, those were kind of foreign notions of land use.

And that was forced upon us tribes as our lands were diminished in those treaties and promises were broken, we were forced into agriculture, or we would lose our land.

And a lot of that included livestock production.

And so, challenging some of these land use paradigms and the ideas of exploitation are still a bit foreign as we think about restoring our languages, restoring our culture, revitalizing our connection to buffalo.

It's much more ecological, it's much more holistic, and it kind of gets us back to some semblance of that, that, that wildlife economy or buffalo economy that is more restorative rather than exploitative.

And so, I think as we think about including indigenous perspectives in land use and management, we can draw from that ecological relationship.

You know, when we protected wolves and bears on the reservation, it was because our elders told us that those wolves and bears taught us a lot about how to be good human beings where we get our medicines from, and that they have a right to be here as much as we do.

And so, it kind of gets to Dan's point about, you know, we as human beings being part of this ecosystem rather than being above it or the only ones who can dictate it.

So, it's-it's much more of an opportunity for us, I think, to engage what we call now traditional ecological knowledge or Indigenous science because Indigenous people were we're very good scientists, but it was based in a different philosophy, one of interconnectedness and-and reciprocity.

So, I think, you know, we need to consider those types of perspectives more today.

WOODRUFF: And Ken is as someone who's spent your life telling the American story, how hard has it been to confront that the ugly side as well as the-the wonderful side we all like to celebrate?

BURNS: Well, you know, I think it's been there, Judy, all along in almost all the stories we've tried to tell.

Here it is so pronounced because it is us deciding that we're the dominant species, that we don't have to live in harmony, that these animals, particularly the buffalo, are not our kin, but something else.

And-and we have an acquisitive and a rapacious sort of attitude towards the continent that we were taming.

And even that in itself, the notion of taming and the fact that this animal is so intricately intertwined with the story of native peoples.

You know, we-we think of this story is as in three acts and our film is just the first two acts.

The first is the buffalo and their interrelationship and then their destruction and then the saving of it as a species on the brink of extinction.

But the next act is really where it's all going to happen.

And Roz and Dan and Jason are on the front lines of that story and are going to be able to take it.

The next hurdle to get to the next space where it's okay to save it.

But what are we going to do after it's saved?

What kind of ecologies and ecosystems are we going to practice and create in order to make sure that at least part of this American Serengeti is returned to what it once was or a semblance of what it once was, not just with the megafauna, but with all of the flora that Roz is talking about, all of those plants that grow in the disturbed areas.

What a wonderful gift that would be if we could sort of arrest our own tendencies and try to see things or try to yield and-and permit our-our brothers and sisters here to tell us now how we might do it a little bit better than the disastrous way we've done heretofore.

WOODRUFF: Well, that is a perfect point at which to turn to our third and our final clip from the film.

Although they came perilously close to extinction, the buffalo survived.

As we see in this next clip, by the early 1900's there was a growing national recognition of the need to preserve the buffalo...

Even with an unclear understanding of how to do that and a recognition of the buffalo's special role in American identity.

NARRATOR: In 1913, the United States came out with a new design for the nickel, done by the sculptor James Earle Fraser.

Fraser said he wanted a coin "that could not be mistaken for any other country's coin."

On one side, the new nickel showed the profile of an American Indian.

On the other was an American buffalo, modeled after a bison Fraser saw in New York City's Central Park Menagerie.

RINELLA: We know its name, it was called "Black Diamond."

And it lived in a cage.

And he uses it as his model.

And it was sold to a butcher.

And the model for the buffalo head nickel was processed and parted out, and sold as meat, in the Meatpacking District in Manhattan.

And it opens up this idea of just how conflicted the symbol is.

We look at it and we see a symbol of wilderness and a symbol of the wanton destruction of wilderness.

You look at that old nickel, there's a buffalo.

At one time, they almost wiped them to extinction.

Why did the European put that buffalo on that nickel?

Was it just a curiosity or was it something that kind of meant something to them in an odd way.

So, in my confusion, and my need to understand is: do you have to destroy the things you love?

NARRATOR: By 1933, the Am erican Bison Society reported that 4,404 buffalo existed in 121 herds in 41 different states.

Half of them were grazing in now nine government-protected herds.

Compared to the millions of buffalo that had once covered the Plains, those were tiny numbers; but enough, and in enough different places, that the Bison Society began making plans to disband, declaring that the American buffalo was finally safe from extinction.

O'BRIEN: This Society was successful, but their understanding of the problem was really short-sighted.

They didn't know about ecosystems.

They thought, if you've got a buffalo, you've saved him.

That's not it.

You've got to save their habitat.

NARRATOR: That same spring of 1933, 75 calves were born on the Na tional Bison Range in Montana.

One of them, a little bull, had blue eyes and white hair, a genetic rarity.

PABLO: A white buffalo is so sacred and so full of hope, and goodwill for the tribes.

Just a huge blessing.

It was a tremendous gift from Creator.

NARRATOR: The staff at the Bison Range called the little bull "Whitey" at first, and its presence turned the preserve into a tourist attraction for a while.

But to the Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreilles on the Flathead reservation, and to virtually all other Native tribes, a white buffalo was mo re than a statistical oddity.

It had special spiritual power and sacred meaning.

It was considered "big medicine" and that became his name.

PABLO: I was three years old.

My grandpa and my dad took me to the bison range and wanted me to touch him.

He was so old; he stood inside this fence, and he didn't move.

I touched him and I thought he would be soft, his head, like, my teddy bear.

And it was bristly.

And that was my first impression, was he's big and I love his eyes.

And he's bristly.

WOODRUFF: And so, at some point, the tide turned in this country.

Roz, I want to ask you, what is your understanding of when things began to turn, when-when there was a wider understanding that the Americans had gone too far in what they'd done to the buffalo?

LaPIER: Yeah, I mean, it really was this early kind of 20th century and late 19th century that we saw this kind of change over in America that started really in the east, as has been, is when people see the film.

It's mentioned in the film.

You know, there's this story of people from the East Coast who are beginning to look towards the West, began to see it in a different with a different viewpoint, even nostalgically of what is what they've lost and thinking about how they can address that.

At the same time period, Indigenous people themselves are transitioning, right?

They're transitioning from living, having that lifestyle of living with bison for those thousands of years to now living mostly on reservations, but also in other communities and no longer being in this world where bison is very central to their lifeways and their religion again and their religious practice.

One of the things that I learned from looking at the stories of my grandparents and looking at the stories of their parents, is that what Indigenous people wanted to share with these same folks like George Bird Grinnell and his, and his "Forest and Stream" magazine, and the folks that he published there was that Indigenous people wanted to tell their story even then in the early 20th century.

And what Indigenous people were sharing was this deep, long relationship with the natural world, with that connection through religion and religious practice and how they thought about a lot of different parts of the natural world.

But including that story with Bison, as Dan has already mentioned, you know, one of the things that Indigenous people thought about bison differently is that they were kin and that was a literal relationship.

WOODRUFF: Jason, what about that?

I mean, how do you pick up on this, this complicated and partly ugly, certainly beautiful over thousands of years, but in more, more recent times, not a pretty story at all.

How do you how do you pick up the story from here?

BALDES: Well, we have to consider that there's 350,000 bison now, but they're-they're essentially in the commercial meat market, so they're ranched animals.

The Department of Interior manages some conservation herds.

And then there's the tribes, you know, working to restore buffalo back to our communities through organizations like the Intertribal Buffalo Council.

But there is a wide spectrum of-of restoration efforts across Indian Country and across private lands and across public lands.

And really the, you know, the buffalo is still ecologically extinct.

It doesn't exist in large numbers on large habitats.

And from a conservation perspective, you know, that's a very important effort to get animals restored from their ecological keystone role on the landscape, but also ensure that you know, we're thinking about the-the important genetics of places like Yellowstone.

The, were the-the remnants of those once vast herds where those genetics exist and ensuring that we can get those animals out for the genetic heterogeneity, improving our overall herd health and the bison species itself are restored in a way that allows them to exist for us the way the one above intended.

And that relationship that we as people have with that animal, restoring that, ensuring that our young people understand the complex history, but also our role now as caretakers, that-that, you know, buffalo took care of us, now it's our turn to take care of them.

And in that, we have to restore land that's land acquisition.

And we also have to change how many of our lands get utilized.

Many of our lands on our on our reservation have been prioritized for-for cattle production, despite them being on an Indian reservation so challenging the status quo and-and thinking about a new future.

You know, the majority of our young people are not farming and ranching and they're not going to go into that any more than our grandma's and grandpa's wanted to 100 some years ago.

So how do we create a better future for our people and for our communities?

You know, restoring that relationship to buffalo is one way, and that is foundational to who we are.

It's in our songs, it's in our ceremonies.

For the very first time this year, we've been able to harvest our own animals for our annual Sundance's.

Is that's a very critical step in restoring that relationship and ensuring that that that meat, which is the most nutritious, the highest in protein, minerals, and vitamins and-and lowest in fat and cholesterol, that that is essentially a way for us to help do away with diabetes, heart disease.

So, as we restore them to the land which they obviously heal as a keystone species, they in turn will begin to heal us as-as we restore that relationship.

WOODRUFF: The circle of life is and, you know, as you've so eloquently put it, Dan, I want to come back to you why does it matter that we care about what happens to the buffalo?

FLORES: I've long thought that when buffalo were finally gone, and this would certainly have been true for almost all Native people who had been engaged with buffalo for-for so many centuries.

That and certainly true, I think, for the America and the emerging American conservation community.

It was as if some titanic sound that reached to the heavens had stopped just at the moment that we turned to listen to it.

And it was a shock, I think, to many people... Obviously, Native people were-were the ones who bore the brunt of the effect of losing that titanic sound.

But many other people felt it as well.

I think that's why we ended up with an American Bison Society that attempted to restore buffalo or at least preserve them as an emblem of what we had lost.

But that's essentially about as far as their thinking ever got.

I mean, to me, one of the things that was happening in America at this time is that we were still tending to model ourselves after the old world after Great Britain and France and Germany and all those countries had lost all their big, wild, charismatic animals.

And even though Teddy Roosevelt had implemented this great new Public Lands System that allowed the United States to do something completely different, to actually preserve some of our really big creature's wolves, bears, bison, if we had allowed it, elk.

Bison certainly represented, as I think Frazier's nickel indicated, that it was the creature that much of the world associated with the United States.

That's why the bison has become our national mammal here in the last decade.

But we didn't want to allow it to be a wild creature.

And that kind of becomes the-the story that takes us up to the present.

WOODRUFF: Ken Burns, there's so much to think about here.

What-what ultimately do you want your, you want Americans who are watching this, anybody watching this film, to know about the buffalo... Its relationship to this country and how we should think about it going into the future?

BURNS: Well, let me just riff off Dan for a second and just go back to that 1913 nickel, right.

On both sides of that coin that we are now beginning to fetishize the Native American and the buffalo.

We're now missing them.

There's something lost.

It's a, it's-it's obscene in a way.

We've spent the last century doing everything we can to eliminate both.

And our buffalo policy and our Native American policy are intertwined and they're designed to reduce the buffalo to nothing and to reduce Native Americans to reservations and change entirely their way of life.

Somewhere along the line, there were a few people that were beginning to-to realize they needed to make a journey.

You know, you can go back to Theodore Roosevelt, who comes down to us is the greatest conservation president.

He was not there before.

He did not have any respect for native peoples whatsoever.

He assumed that the buffalo's extermination would heed the ability to assimilate Native Americans into our culture.

And he had to learn.

And so, I think in the arc of the life of Theodore Roosevelt, it's not just he arrives on the scene fully evolved that this is a journey that we have to take.

WOODRUFF: Roz, I mean, where do you see this going with-with Native Americans in relationship to the buffalo and in relationship to this country?

LaPIER: Yeah, I mean, it's-it's I think it's, is a great time to really, again, look at our past, right?

But I think that in looking at past actions of American citizens, we also then, to look further back, and look at the Indigenous people that were here... Look at their landscape management practices.

Look at the relationships that they had with the world around them and the natural world.

The first thing that needs to happen is we need to have the land right.

We need to have healthy land, a large landscapes, good habitat.

And for at least for the bison, a lot of different prairie grasses that they eat.

And so, when we think about bison and Dan's really great story about, you know, let's ask the bison what they want.

And yes, they want to come back, but not as cows, not as cattle.

They do want to be free.

But for that to occur, for them to be truly animals that get returned to the American landscape, they need large areas for them to be able to do that.

We still don't have that, as has been mentioned by Jason.

You know, a lot of the practices we have today is that bison are on these very small parcels of land where they are allowed to be free but still very small.

And so, we need to start thinking bigger when we, when we think about this.

And I think that we are at a point in our history in America where there are a lot of people who are interested in all of these things, interested in looking at Indigenous knowledge as a tool, as a management tool, and looking at our past as America and really thinking about it seriously and thinking about how to address some of those things that have happened in the past and then that kind of hope for the future only because we understand these things so much better.

WOODRUFF: And finally, to you, Jason, is that a future that Roslyn describes, that that is likely?

That's-that's more than possible, but it's probable?

BALDES: I certainly am optimistic that it is organizations like the Intertribal Buffalo Council, you know, now with 83 member tribes across the country.

ITBC is a 30-year-old organization that's restored 25,000 buffalo to 65 herds in 20 states.

There, that efforts going to continue.

Our main goal there at ITBC is to restore buffalo to Indian Country for the cultural and spiritual purposes, and that's going to continue to increase.

We want to get buffalo into our school lunch programs.

We want to provide it for our community and elder programs.

And then there's-there's the conservation effort.

You know, there's of organizations like the National Wildlife Federation, you know, really strategically working to support the sovereignty and self-determination of tribes across the country.

Other conservation NGOs are doing the same.

We have federal directives now at the at the national level working to support tribal buffalo restoration.

We need to, you know, enhance that and continue to build from there.

You know, and I think what we're doing in terms of restoring the buffalo to various landscapes across Indian Country can really permeate what opportunities we can create on public lands.

And there's a lot of discussion about that, especially out west, where, you know, many of our lands have been prioritized for-for economic reasons and exploitative reasons.

And as we kind of, you know, rehash what it is we want to see by bringing science in and technology and thinking more ecologically that there's elements that we can, we can bring together and really work to create a better future for our young people.

And I think, you know, whether whatever our background is, what-what tribes, nations, communities, we come from, that that's a common thread.

We want to create a better world for our children.

And so, I think that many of us do that with buffalo, and we can, we can use that as a model for Americans to have a-a relationship, some reciprocity, some understanding of our Indigenous science so that we do create and leave a better world here for-for the future generations.

WOODRUFF: And on that uplifting note, let me thank you, all four, for such a wonderful, such a rich discussion.

Thank you so much, to Rosalyn LaPier to Dan Flores, to Jason Baldes, and, of course, to our filmmaker Ken Burns.

Thank you, thank you so much.

FLORES: Thank you, Judy.

BURNS: Thank you, Judy.

WOODRUFF: And thanks to all of you for watching.

And do remember to tune into Ken's film, "The American Buffalo", premiering on your PBS station and on the PBS app, on October 16th.

I'm Judy Woodruff, thank you for joining us.

(music plays through credits) FUNDING: The Better Angels Society is proud to support this presentation of "The American Buffalo: A Story of Resilience" part of the "Ken Burns Public Dialogue Initiative at Georgetown University."

Support for PBS provided by:

Corporate funding for The American Buffalo was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and its...