“The Golden Door” (Beginnings-1938)

Episode 1 | 2h 8m 43sVideo has Audio Description

Reversing open borders, a xenophobic backlash prompts Congress to restrict immigration.

After decades of maintaining open borders, a xenophobic backlash prompts Congress to pass its first laws restricting immigration. Meanwhile, in Germany, Hitler and the Nazis begin their persecution of Jewish people, causing many to try to flee to neighboring countries or America. Franklin Roosevelt and other world leaders are concerned by the growing refugee crisis but fail to coordinate a response.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate funding provided by Bank of America. Major funding provided by David M. Rubenstein; the Park Foundation; the Judy and Peter Blum Kovler Foundation; Gilbert S. Omenn and Martha A....

“The Golden Door” (Beginnings-1938)

Episode 1 | 2h 8m 43sVideo has Audio Description

After decades of maintaining open borders, a xenophobic backlash prompts Congress to pass its first laws restricting immigration. Meanwhile, in Germany, Hitler and the Nazis begin their persecution of Jewish people, causing many to try to flee to neighboring countries or America. Franklin Roosevelt and other world leaders are concerned by the growing refugee crisis but fail to coordinate a response.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The U.S. and the Holocaust

The U.S. and the Holocaust is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipAnnouncer: Funding for "The U.S. And the Holocaust" was provided by David M. Rubenstein, investing in people and institutions that help us understand the past and look to the future; and by these members of the Better Angels Society: Jeannie and Jonathan Lavine; Jan and Rick Cohen; Allan and Shelley Holt; the Koret Foundation; David and Susan Kreisman; Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder; the Fullerton Family Charitable Fund; the Blavatnik Family Foundation; the Crown Family Philanthropies, honoring members of the Crown and Goodman families; and by these additional members.

By the Park Foundation; the Judy and Peter Blum Kovler Foundation, supporting those who remind us about American history and the Holocaust; by Gilbert S. Omenn and Martha A.

Darling; by the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, investing in our common future; By the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and by viewers like you.

Thank you.

♪ Narrator: On a sunny March afternoon in 1933, a German businessman and his family went for a stroll in the center of Frankfurt.

Otto Frank snapped a picture of his wife, Edith, and their two daughters-- Margot, 7 years old, and Annelies, just 3.

Otto's ancestors had lived in Germany since the 16th century.

Merchants and bankers, they were not particularly observant Jews.

Otto, a proud officer in the Great War, was a patriotic German.

But in January of 1933, Adolf Hitler had come to power and everything had begun rapidly to change.

Jews, Hitler charged, were "parasites," not Germans.

Nazi thugs roamed the Frankfurt streets, beating anyone they thought was Jewish.

Most of the Franks' Gentile friends fell away.

Their landlord insisted they find other quarters.

Margot was made to sit apart from her classmates in school.

Man as Frank: The world around me had collapsed.

When most of the people of my country turned into hordes of nationalistic, cruel, antisemitic criminals, I had to face the consequences, and though this hurt me deeply, I realized that Germany was not the world, and I left forever.

Narrator: By the time Otto Frank photographed his family, he and Edith were already planning to move to Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

By early 1934, they would be living in a spacious, sunny apartment in the city's River Quarter, alongside hundreds of other Jewish families from Germany.

They would eventually try to seek a safe haven in the United States, only to find, like countless others fleeing Nazism, that most Americans did not want to let them in.

♪ [Gulls squawking] [Ship's horn blows] Woman: Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand a mighty woman with a torch, whose flame is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles.

From her beacon-hand glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command the air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

"Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!"

cries she with silent lips.

"Give me your tired, your poor, "your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, "the wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

"Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

Emma Lazarus.

Narrator: In 1883, Emma Lazarus, the descendant of Portuguese Jews who had fled the Inquisition and found sanctuary in Manhattan before the American Revolution, had written a poem expressing what the Statue of Liberty meant to her.

But a few years later, Thomas Bailey Aldrich, a writer whose family had also lived in America since colonial times, wrote another poem warning of what he believed would happen to his country if the golden door remained open.

Man as Aldrich: Wide open and unguarded stand our gates, and through them presses a wild, motley throng.

In street and alley what strange tongues are these, accents of menace alien to our air, voices that once the Tower of Babel knew!

O Liberty, white Goddess!

is it well to leave the gates unguarded?

Man: I think Americans have a very hard time deciding what kind of country they want to have.

We all tend to think of the United States as this country with the Statue of Liberty poem, "Give me your tired, your poor."

But in fact, exclusion of people and shutting them out has been as American as apple pie.

♪ Man: All of my grandparents are immigrants from Eastern Europe except one grandmother was born here.

So, I sort of grew up haunted by stories of, as they used to say, the old country.

Haunted by this story of my grandfather's brother and his family, living in a provincial town in Eastern Poland, and then they disappeared.

All you think about is that they had been consumed by this conflagration that consumed all of Europe.

♪ ♪ Narrator: When Nazi rule began in 1933, there were 9 million Jews in Europe.

12 years later, when the Second World War ended in 1945, at least two out of every 3 of them had been murdered.

Mendelsohn: It's not so easy to put the picture together, the real scale of what happened to people.

It is unbelievable.

It boggles the imagination.

You don't know what 6 million people looks like.

Narrator: As the catastrophe of what would come to be called the Holocaust unfolded, Americans heard about Nazi persecutions of Jews and others on the radio, read about it in their newspapers and magazines, and glimpsed it in newsreels.

Some Americans responded by denouncing the Nazis, marching in protest, and boycotting German goods.

Individual Americans performed heroic acts to save individual Jews.

Some government officials battled red tape and bigotry to bring Jewish refugees to America.

In the end, the United States admitted some 225,000 refugees from Nazi terror, more than any other sovereign nation took in.

And by defeating Nazi Germany on the battlefield, the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and their allies stopped the killing of the surviving Jewish people in Europe.

But during the years when escape was still possible, the American people and their government proved unwilling to welcome more than a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of desperate people seeking refuge.

Woman: The Holocaust disrupts any idea that we have of good and evil, of right and wrong.

This is a story in which everyone is challenged all the time.

We are challenged as Americans.

We're challenged as parents, as children.

We're challenged as neighbors and as friends to think about what we would have done, what we could have done, what we should have done, and even though the Holocaust physically took place in Europe, it is a story that Americans have to reckon with, too.

Man: We tell ourselves stories as a nation.

One of the stories we tell ourselves is that we're a land of immigrants.

But in moments of crisis, it becomes very hard for us to live up to those stories.

I think the impetus should not then be to wag your finger at people in the past and think that we're somehow superior to them, but to struggle to understand why that's such a tension between having a humanitarian ideal and then living up to it on the ground.

Woman: Part of our national mythology is that we are a good people, we are a democracy, and we are a democracy, and in our better moments, we are very good people.

But that's not all there is to this story, and I think if we're going to congratulate ourselves on our democracy, which I think we should, we also need to face up to the other side.

Woman 2: In the past few years, I've begun to wonder how serious America's commitment to looking at some of the dark marks in its history really is.

How can we learn from the past?

Where did we go wrong?

How can we not go wrong the next time?

And I think while there is much we can be proud of of this country, the episode of America and the Holocaust is not one that redounds to our credit.

Man: How did America treat its potential refugees?

The refugees, they lost their lives because those doors-- the golden door was not wide open.

♪ [Birds chirping] [Horse neighs] Narrator: For centuries, America had mostly open borders.

Peoples from Europe and the Far East were let in-- and at least tolerated-- as workers, farmers, soldiers, and pioneers needed to conquer a continent and build a nation.

Irvin Painter: This is the good side of us, the open side of us.

We want to welcome working people.

The other side of that is Native American genocide, Native Americans being pushed out of their lands.

And then there's also the involuntary immigrants, the Africans who were transported across the ocean to become a workforce that could be worked to death.

So, the idea of immigrants at the top, it looks very good, but that's not all there is to us.

Narrator: Before the Civil War, most immigrants had come from northern Europe-- England, Scotland, Ireland, Germany, Holland, and Scandinavia.

Hayes: I'm named after my ancestor who arrived at the port of Boston in 1860.

He came from County Cork in Ireland.

He didn't have to fill out anything but a landing card when he got here in a time when immigration was free and open.

It became more and more restrictive later.

Narrator: In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first time the United States had barred the immigration of any people from anywhere.

But between 1870 and 1914, nearly 25 million people would arrive, mostly from Southern and Eastern Europe.

They spoke unfamiliar tongues, followed other customs, worshipped God in different ways.

Their sheer numbers inspired a backlash.

Man: We Americans must realize that the altruistic ideals which have controlled our social development during the past century, and the maudlin sentimentalism that has made America "an asylum for the oppressed" are sweeping the nation toward a racial abyss.

This generation must completely repudiate the proud boasts of our fathers that they acknowledged no distinction in "race, creed, or color" or else turn the page of history and write: "FINIS AMERICAE."

Madison Grant.

Daniel Okrent: They don't speak our language.

They don't really look like us.

They don't have the educations that we have.

And so, you find somebody like Henry Adams walking across Boston Common and he describes in his autobiography, he sees this creature, this furtive Yitzhak or Yakov reeking of the ghettos, snarling in a guttural Yiddish.

What was this thing?

It was utterly alien.

Narrator: Among the new arrivals from Eastern Europe were more than two million Jews, most fleeing poverty, and many escaping antisemitic violence.

Some Jews, who had already been in America for generations, were also wary of the newcomers.

"We are Americans and they are not," one rabbi said.

"They gnaw the bones of past centuries."

By 1910, New York would be home to more than a million Jews, more than a quarter of the city's population, far more than any other city on earth.

Hayes: The anxieties about urbanization, about unlettered, untutored, relatively uneducated peoples coming in in large numbers, the sense that disease was a problem, all of these worries were amalgamated into a belief that immigrants cause these problems, and thus immigration should be held down.

Narrator: Many white Protestant Americans came to fear they were about to be outnumbered and outbred by the newcomers and their offspring-- that they were being replaced.

They embraced a new pseudo-science born in Britain called eugenics, which falsely claimed with no evidence that everything from poverty to prostitution, disabilities to what they called feeble-mindedness could be eliminated if the individuals they dismissed as "socially defective" could be stopped from reproducing.

Man: I wish very much that the wrong people could be prevented entirely from breeding; and when the evil nature of these people is sufficiently flagrant, this should be done.

Criminals should be sterilized, and feeble-minded persons forbidden to leave offspring behind them.

Theodore Roosevelt.

Irvin Painter: The idea was that the bad people have to stop reproducing and the good people need to reproduce more.

Negative eugenics says sterilize the wrong people, snuff them out, and that's the eugenics that the Nazis would pick up on.

Narrator: Colleges and universities taught eugenics.

Medical societies confirmed it.

Clergymen preached it.

John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie funded it.

And some of the most prominent people in America championed it-- Margaret Sanger, Alexander Graham Bell, even Helen Keller.

Woman as Keller: It seems to me that the simplest, wisest thing to do would be to submit cases like that of the malformed idiot baby to a jury of expert physicians.

If the evidence were presented openly and the decisions made public before the death of the child, there would be little danger of mistakes or abuses.

We must decide between a fine humanity and a cowardly sentimentalism.

Narrator: 33 of the 48 states would eventually enact eugenics laws mandating the forced sterilization of wards of the state deemed physically or mentally "unfit"-- people in prisons, hospitals, and asylums.

More than 60,000 Americans would be sterilized without their consent before the last of these statutes was removed from the books in 2014.

Eugenics also provided a racist rationale for those convinced immigration needed to be drastically curtailed.

Man as Grant: The man of the old stock is being crowded out of many country districts by these foreigners just as he is today being literally driven off the streets of New York City by the swarms of Polish Jews.

These immigrants adopt the language of the American, they wear his clothes, they steal his name, and they are beginning to take his women, but they seldom adopt his religion or understand his ideals.

And while he is being elbowed out of his own home, the American looks calmly abroad and urges on others the suicidal ethics which are exterminating his own race.

Madison Grant.

Narrator: Madison Grant was a widely-admired conservationist-- a friend of presidents, a founder of the Bronx Zoo, responsible in part for saving the California Redwoods and preserving the buffalo, and instrumental in creating Glacier, Denali, and Everglades National Parks.

Okrent: And he was also a violent antisemite and a violent anti-Italian, and he really was horrified by what he saw happening on the streets of New York.

So, he publishes a book called "The Passing of the Great Race," in which he puts forward the idea that nationalities have eugenic characteristics.

He fills it with all sorts of interesting historical, so-called data, which is mostly crazy, but it's very persuasive and it does give the anti-immigration movement, it suddenly gives them science.

"Science says if we let them in, then they're going to destroy the American gene pool."

Narrator: For Grant and many others, Jews were a distinct race, not considered white, dismissed as "uncouth Asiatics."

Grant's supposedly "scientific" claims about a rigid hierarchy of races was ludicrous-- the biological notion of race itself is a fiction-- but his ideas caught the imagination of those Americans already opposed to immigration.

Hayes: People tended to increasingly view nationalities as if they were breeds or species.

To liken nationalities to breeds was a fundamental categorical mistake.

The biological pool of human beings between Germans and French, Dutch and English is nothing like the biological or genetic pool between poodles and German shepherds.

Narrator: American xenophobia deepened when the U.S. entered the Great War in 1917.

More than 116,000 American servicemen would die in a war that was supposed to end all wars-- and did nothing of the kind.

After the War, the United States was convulsed by white-on-black violence in dozens of cities, anarchist bombings, bloody strikes, and a "Red Scare" that saw the arrests of 10,000 suspected revolutionaries, many of them immigrants, some of them Jewish.

Irvin Painter: Anti-immigrant sentiment and the Red Scare came together, so, by the early Twenties, you have this boiling notion that immigrants are stupid and immigrants are bolshevists and immigrants are threatening America.

Hayes: And this justified increasingly in the minds of people like Madison Grant and Henry Cabot Lodge, the senator from Massachusetts, who argued that the way to master the problems was to restrict the inflow of these destabilizing populations.

Narrator: Antisemitism intensified.

The automobile pioneer Henry Ford blamed Jews for everything from Lincoln's assassination to the change he thought he detected in the flavor of his favorite candy bar.

He bought himself a weekly newspaper, the "Dearborn Independent," and used it to spread his antisemitic propaganda.

In a series of 91 weekly articles called "The International Jew," he promoted "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion," a Russian hoax that claimed there was a global Jewish conspiracy to take over the world.

The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia had only seemed to confirm those fears.

The articles were eventually reprinted in 4 volumes and translated into 9 languages, including German.

Ford's newspaper continued printing its antisemitic bile and had the second-highest circulation in the country.

Jewish-Americans were already denied membership in private clubs, not hired by banks or prestigious law firms.

"Restrictive covenants" kept them out of desirable neighborhoods.

Strict quotas limited the number of Jewish students enrolled in universities and barred all but a handful of Jewish teachers from their faculties.

Hotels advertised rooms only for "Gentiles."

Greene: One of the most, I think, maddening things about antisemitism is an antisemite will hold a contradictory belief and it won't bother the antisemite, right?

So, "Jews are capitalists," "Jews are Communists."

Or, "Jewish men are weak and effeminate," or "Jewish men are a sexual threat to-- to non-Jewish women."

These are contradictory beliefs that are illogical, that don't bother antisemites.

So, how do you fight back against that with logic?

Lipstadt: What are the stereotypes associated with antisemitism?

Something to do with money, something to do with smarts, but not positive or affirmatively, conniving and a small cabal.

Jews are very few in number, but they know how to control things.

They are the puppet masters, controlling the puppets.

Narrator: In the early 1920s, support grew steadily for congressional legislation to permanently restrict immigration, designed to return to the ethnic mix of America as it had been before the waves of newcomers from Southern and Eastern Europe.

A resurgent Ku Klux Klan, now several million strong, as anti-Catholic and antisemitic as it was anti-Black, favored restricting immigration.

So did many Protestant clergymen and union leaders convinced immigrants drove wages down.

President Calvin Coolidge supported it, too.

"America must be kept American," he said.

Jewish and Catholic organizations were adamantly opposed.

A small band of congressmen-- mostly from urban districts, often immigrants themselves or the children of immigrants-- tried to speak for the new Americans they represented.

Man: I knew them.

I knew the Irish and the Jews and the Italians and the Greeks.

I knew the women in the Brooklyn tenements who scrubbed their floors again and again in the helpless fight against squalor.

I knew their richness and their laughter and the disappointing heartbreak of the struggle in America to adjust.

I knew also their pride, the unfulfilled dream of independence that had first brought them here.

Emanuel Celler.

Narrator: Freshman Congressman Emanuel Celler was a third-generation Jewish-American, who represented Brooklyn's 10th District.

It was one of the most ethnically diverse in the nation, and he liked to tell his constituents that his Catholic grandfather had jumped into New York Harbor to save his Jewish grandmother from drowning after the boat they had both taken from Germany began to sink.

When Celler came to Washington in the winter of 1923, he hurled himself into the struggle against the latest anti-immigration bill, even before he was able to hire a staff.

He pored over books in the Library of Congress and brought in scientists to testify against eugenics.

The work of Madison Grant and his fellow eugenicists, Celler said, was all "bunk and balderdash."

"There is no such thing as superior and inferior races.

One set of people is as good as another."

Man as Celler: This is indeed a new doctrine for a democratic America, founded on the declaration that all men are created equal, a slap in the face to our immigrants who have assimilated and who have become bone of our bone, flesh of our flesh.

Narrator: But nothing Celler or his allies said could halt the rush toward passage.

The new law, the Johnson-Reed Act, passed by overwhelming margins in both the House and Senate.

On May 26, 1924, Coolidge signed it into law.

It drastically limited the total number of immigrants admitted to the United States, and it allotted quotas to each country, overwhelmingly favoring immigrants from Northern European countries.

Erbelding: The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924 is really meant to define who is going to be an American in the future.

And 85% of it is for people who are born in countries that they decide in 1924 are white Protestant countries that will send white Protestant immigrants to the United States.

Narrator: The act did not limit immigrants from the Americas-- who were needed for farm labor-- but it now barred all Asians, not just the Chinese.

One Japanese newspaper labeled the law's passage "the greatest insult in our history," and a prominent nationalist declared it made "an eventual collision between Japan and America...inevitable."

For the first time, before embarking for the United States, potential immigrants would have to obtain a visa from American consulates in their countries, giving State Department bureaucrats unprecedented control over who was and who was not worthy of admission.

The new act also made no exception for refugees-- those fleeing disaster, war, or persecution.

In 1921, 805,000 immigrants had come to America.

In 1925, under the new quota system, just under 150,000 were allowed in.

There was no explicit quota for Jews, and Jews were not specifically named in the law.

But it was not an accident that most recent Jewish immigrants had come from the Eastern European countries that now had miniscule quotas.

Almost 120,000 Jews had started new lives in the United States in 1921.

5 years later, only 10,000 were able to do so.

"America has closed the doors just in time "to prevent our Nordic population from being overrun by the lower races," said Madison Grant.

"The law's passage was one of the greatest steps forward in the history of this country."

Man as Celler: To say that a handful of men forced through the Immigration Act of 1924 is false.

The United States was drawing her skirts about her in fear lest she be contaminated by the alien.

The temper of the Congress, I discovered, is the temper of the country.

Emanuel Celler.

Narrator: In 1924, in a prison cell in Landsberg, Bavaria, Adolf Hitler, the head of the National Socialist German Workers Party-- the Nazis--learned of the new American immigration law.

He had been imprisoned for high treason after leading a failed coup.

He was pleased that the United States felt itself to be what he called a "Nordic-Germanic state," and had acted to preserve its purity by "excluding certain races."

Those ideas mirrored Hitler's own beliefs, and he was willing to exploit the chaos that gripped Germany after its defeat in the Great War to promote them.

At Versailles in 1919, the victorious Allies had imposed on the Germans a treaty that required them to give up 10% of their territory as well as their colonies in Africa, pay massive reparations, and disarm completely.

Hitler, who had been an obscure army dispatch messenger when the war ended, was among those who convinced themselves Germany had not been defeated on the battlefield, that she had been "stabbed in the back" by socialists and Jews.

While behind bars, Hitler worked on a book entitled "Mein Kampf"-- "My Struggle."

History, he argued, was an endless racial conflict in which the superior so-called "Aryan" race was being undermined by Jews.

Hayes: The most dangerous of other nationalities, said the Nazis, were the Jews.

And the reason they were was not only inherited, that is, there had been a Christian teaching that these people are corrupting and so forth.

The reason is also they were the people who brought the notion of conscience, the golden rule, fair play, international cooperation into the world.

Man: What's particular about the thing that Hitler puts together is to say, "The Jews are responsible for every global idea, "for every universal idea.

"Anything which allows us to see each other as people, rather than as members of a race, that's the Jews."

Narrator: Germany's 523,000 Jews constituted less than 1% of their country's population.

But 100,000 of them had fought during the Great War.

12,000 had died.

They had overcome centuries of persecution to become merchants, manufacturers, musicians, lawyers, writers, scientists, artists, government officials, and were loyal Germans.

Stern: We were absolutely integrated into this town of about 65,000 inhabitants and felt completely at home.

Narrator: The city of Hildesheim, in northern Germany, was home to some 1,000 Jewish families.

Julius Stern owned a small shop.

His wife Hedwig was the daughter of a well-to-do-merchant.

They had 3 children.

Their oldest was Günther, born in 1922.

Stern: My mother was a absolute luminous woman.

And she could write German verses for all occasions and was praised as the "Poet Laureate" of our family.

I had a neighbor boy who was my best friend on the slim basis that both of our names were Günther.

His family was not all that conservative as Protestants.

And we were not that observant as Jews.

Narrator: But to Hitler, all Jews were clannish, stateless, subhuman "leeches" who drained the strength of every country in which they lived.

From his cell, he promised to one day make Germany free of them--and, by so doing, restore Germany's greatness.

Victory in that struggle, he said, demanded military might, "Aryan fertility," and racial purity.

He would seek to destroy the power of what he believed was a worldwide conspiracy-- "International Jewry."

At the same time, he dreamed of reclaiming German territories and waging a war against the Soviet Union that would simultaneously destroy what he called "Jewish Bolshevism" and win for Germany the "Lebensraum"--Living Space-- to which he believed it was entitled.

Hayes: Hitler saw the expansion of Germany into Eastern Europe as foreshadowed by what we had done in North America, the expansion of the white people of the United States across the continent from east to west, brushing aside the people who were already here and confining them to reservations.

Narrator: "The immense inner strength" of the United States, Hitler said, came from the ruthless but necessary act of murdering native people and herding the rest into "cages."

Snyder: He saw us as the way that racial superiority is supposed to work.

The higher races conquer the territory.

So, if anything, the attitude before the war was an attitude of a certain admiration.

Narrator: Hitler hoped that just as the Americans had conquered "the Wild West," his countrymen would conquer "the Wild East"-- Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

"Our Mississippi," he said, "must be the Volga."

Germans would sweep aside those who inconveniently occupied those lands-- Poles and other Slavs, as well as Jews-- much as Native Americans had been swept aside.

When Hitler was released from prison in December of 1924, the fledgling Weimar Republic that had been born at the end of the Great War was finally coming into its own.

Berlin, its capital and largest city, home to 1/3 of Germany's Jews, had become the intellectual and creative center of Europe-- Expressionism on canvas and on the movie screen, Bauhaus architecture and American jazz, scientific advancement and avant-garde music, sexual freedom and leftist politics.

Berlin represented everything Hitler hated and hoped to destroy.

♪ In the autumn of 1929, after nearly a decade of unprecedented economic growth, the New York stock market crashed.

The Great Depression that followed would be the worst crisis America had faced since the Civil War.

Before it was over, one out of every 4 wage-earners-- more than 15 million men and women-- would be without work.

Now Americans were even less eager to welcome workers from foreign lands than they had been before.

President Herbert Hoover directed all overseas consulates to strictly enforce what had been a seemingly minor provision of the immigration law.

From now on, the United States would deny a visa to any would-be immigrant "likely to become a public charge," dependent on government support.

Under the slogan "American jobs for real Americans," Hoover's Labor Department approved raids by sheriffs, marshals, and vigilantes that rounded up some 1.8 million people of Mexican descent and deported them.

It was called the "Mexican Repatriation Program," but 6 out of 10 of those dispossessed are believed to have been American citizens.

In 1932, for the first time in American history, more people left the United States than were allowed in.

Man: You are approaching Ellis Island, once the gateway for thousands seeking fortune, and now every month sees hundreds banished after being convicted by the immigration board of failing to meet the requirements of good citizenship.

Today's batch of deportees include a husband and wife, forced apart by Uncle Sam's stern edict.

And so the symbol of liberty becomes a fading memory of things that might have been.

♪ Narrator: The Great Depression spread relentlessly around the world.

In Germany, more than a third of the adult population was without work.

Parliamentary democracy seemed powerless to improve things.

The Weimar Republic was teetering.

Governments came and went.

The search for scapegoats intensified.

In the chaos, Hitler saw his chance.

[Hitler speaking German] [Crowd cheering] Narrator: In 1928, the Nazi share of the vote had been less than 3%.

By 1932, theirs was the largest party in Germany, but still not large enough to form a government.

To appeal to moderates, the Nazis downplayed their antisemitism and they stepped up street warfare against socialists and Communists to convince voters that civil war was imminent.

Then, a small group of elite conservatives stepped in and on January 30, 1933, saw to it that Hitler was appointed Chancellor-- confident that they could control him.

"We have hired him," one of them told a friend.

"In a few months, we will have pushed him so far into the corner that he will squeak."

They had misjudged him.

Snyder: The people who brought Hitler to power didn't necessarily share all of his ideas.

In fact, they didn't.

But what they did believe was that we can't have democracy anymore, because if we have democracy, then the Left and the labor unions, they're going to take all of the power.

So, the people who brought Hitler to power were conscious and aware, and desirous of doing away with democracy.

[Crowd shouting] Narrator: Within two months, with a ruthlessness that stunned supporters and opponents alike, Hitler bullied the parliament--the Reichstag-- into granting him the powers of an absolute dictator.

The morning after Hitler took power, local Nazis staged victory marches throughout the country.

In Hildesheim, the Stern family's apartment overlooked the parade route.

Stern: We stayed home, and my parents said, "Don't even look out the window."

And at the very tail end of that parade were my classmates.

My father called my brother into our-- what was called the gute stube, which was the best room in the apartment.

And he said to us, "Sit down, boys, I have something to tell you."

And what he said was, "Don't stick out.

He who sticks out, gets stuck."

We took him seriously.

He said, "Be like invisible ink."

In other words, what you are will someday come out again, but at this time, fade into the crowd.

♪ Franklin Roosevelt: I, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States... Narrator: The United States had a new leader that winter, too.

Roosevelt: preserve, protect, and defend... Narrator: Franklin Delano Roosevelt was sworn in as the 32nd president on March 4th.

Roosevelt: This is a day of... Narrator: The economic situation had steadily worsened since 1929, so steadily that some Americans on both sides of the aisle urged the new president also to assume dictatorial powers.

Roosevelt: the Congress shall fail to take one of these... Narrator: In his inaugural address, he assured Americans that "the only thing we have to fear is fear itself," but he also warned that if all else failed... Roosevelt: I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis-- broad executive power to wage a war against the emergency as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.

[Crowd cheering] Narrator: His wife Eleanor remembered that she'd found the crowd's enthusiastic reaction to that line "a little terrifying."

During the 100 days that followed, Roosevelt would sign into law 16 major pieces of domestic legislation that laid the foundation for what he called the New Deal.

His overriding objective was to put Americans back to work.

Foreign policy was left mostly to the State Department-- small, hide-bound, dominated by conservative members of the Protestant establishment.

FDR's secretary of state was Cordell Hull, a former Tennessee senator most concerned with increasing America's trade with the world and opposed on principle to interfering in the domestic affairs of other countries.

[Hitler speaking German] Narrator: Many Germans-- Jews and Gentiles alike-- believed that once in power, Hitler would moderate his views.

They took comfort in an old German saying, "Nothing is eaten as hot as it is cooked."

Others hoped his government would quickly collapse as so many others had.

[Men chant in German] Narrator: The Nazis soon dashed those hopes.

Within weeks of taking power, Hitler's Brownshirt street fighters and black-clad members of an elite paramilitary organization called the Schutzstaffel-- or SS-- had rounded up some 4,800 socialists and Communists and soon sent them to the first of many concentration camps-- guarded compounds initially intended to hold large numbers of political opponents, stripped of all their rights as citizens.

It was set up about 12 miles from Munich, near the village of Dachau.

By year's end, more than 100,000 people had been imprisoned throughout Germany.

Meanwhile, Brownshirts stormed up and down German streets, beating anyone they decided looked Jewish, chanting, "When Jewish blood spurts off the knife, everything will be fine again!"

Man: "Chicago Tribune."

Bands of Nazis throughout Germany carried out wholesale raids calculated to intimidate the opposition, particularly the Jews.

As hundreds have sworn in affidavits, men and women were insulted, slapped, punched in the face, hit over the head with blackjacks, dragged from their homes in night clothes.

Never have I seen law-abiding citizens living in such terror.

Edmond Taylor.

Narrator: American newspapers published more than 3,000 stories about antisemitic incidents during the first 100 days of Nazi rule.

Greene: Americans who picked up their papers, or who listened to the radio, had access to a lot of information about Nazi persecution of Jews.

Is it the lead story?

No.

The Depression in the 1930s is the lead story.

But it's not right to say the information wasn't there.

The information was there.

Narrator: Many Americans were appalled by what they read.

But others were skeptical-- remembering that lurid anti-German propaganda from the Great War had turned out to be false.

Jewish-Americans were deeply divided as to what, if anything, they should try to do about it.

I think a lot of American Jews were torn between wanting to ring the alarm and not wanting to seem alarmist.

They had just precariously established their identities as Americans.

Lipstadt: What's going to make the situation better?

And no one really knew.

They were also continuously told by political leaders, you know, if you speak out and make a fuss, it'll only make it worse.

And there was also the fear, and a legitimate fear, that if we talk too much about this, Americans are going to say, "Well, that's right.

You know, Jews are like that.

Jews are conniving."

Narrator: On March 20th, despite a heavy rainstorm, some 1,500 representatives of Jewish organizations gathered in the ballroom of New York's Hotel Astor, hoping to find consensus about what to do.

When many called for a mass rally at Madison Square Garden and other demonstrations across the country, New York Supreme Court Justice Joseph Proskauer rose to object.

He begged those present to vote against public meetings that could only further inflame Hitler.

The crowd began to boo, but he continued: "I ask you to think whether you want Jewish blood to be seen in the gutters of Germany."

Then Stephen Wise, the best-known rabbi in America, stood up.

Wise demanded that Proskauer apologize for implying that American Jews could ever be blamed for what the Nazis did to German Jews.

Wise had been born in Budapest and was already so celebrated that the post office delivered to him letters addressed only, "Rabbi, USA."

Worldly, charismatic, and a brilliant orator, he had broken from the world of his orthodox ancestors to establish the Reform Free Synagogue in Manhattan.

"The time for prudence and caution is past," he said.

Man as Wise: We must speak up like men.

How can we ask our Christian friends to lift their voices in the protest against the wrongs suffered by Jews if we keep silent?

What is happening in Germany today may happen tomorrow in any other land on Earth unless it is challenged and rebuked.

It is not the German Jews who are being attacked.

It is the Jews.

Narrator: Rabbi Wise prevailed.

The rally at Madison Square Garden was scheduled for March 27th.

Meanwhile, Jewish War Veterans led a march to New York's City Hall, calling for a worldwide boycott of German merchandise.

When Jewish organizations in England echoed their demand, the Nazis claimed that this was proof the Reich was under attack by Jews everywhere.

The Nazis denounced the stories of mistreatment as lies--Jewish lies.

Hermann Goering, one of Hitler's closest advisors, assured the foreign press that the German government had moved against Bolsheviks, not Jews.

No one, he promised, would ever be "subjected to persecution solely because he is a Jew."

And he also ordered German Jewish leaders to call for an immediate end to all "demonstrations hostile to Germany."

Otherwise, Goering said, "We are going to take our revenge.

"The Jews in America and England are hoping to injure us.

We shall know how to deal with their brothers in Germany."

The American Embassy in Berlin cabled Secretary of State Cordell Hull that it was the Nazis who were lying, that the Jewish situation was "rapidly taking a turn for the worse."

But Hull insisted that the mistreatment was coming to an end, that things would "revert to normal" if the protests in America would stop.

Film announcer: Thousands who waited hours behind police lines rushed forward as the doors of Madison Square Garden are opened.

Jews and Gentiles join in the race for seats and 22,000 of them get in.

Narrator: On March 27, 1933, more than 20,000 New Yorkers packed the Garden to show their support for German Jews; 35,000 more gathered around loudspeakers outside.

Christian clergymen denounced the Nazis.

Former New York governor Al Smith, whose presidential candidacy in 1928 had been undercut by anti-Catholic bigotry, equated the Nazis with the Ku Klux Klan: "It don't make any difference to me," he said, "whether it's a brown shirt or a night shirt."

Rabbi Wise was the last to speak.

Man as Wise: If things are to be worse for our brother-Jews in Germany, which I cannot bring myself to believe... then humbly and sorrowfully, we bow our heads in the presence of the tragic fate that threatens, and once again appeal to the conscience of Christendom to save civilization from the shame that may be imminent.

[Crowd cheering] Narrator: Similar rallies were held in Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore, and 70 other cities and towns across America.

More than a million Americans were said to have taken part.

Hitler now claimed that Jews controlled the United States government.

He ordered a one-day boycott of Jewish businesses throughout Germany.

Brownshirts stationed themselves outside shops and office buildings to intimidate anyone who tried to venture inside.

[Men speaking German] Narrator: Again and again, Jewish-Americans would find themselves in an agonizing quandary: if they kept quiet about Nazi persecution, it looked as though they'd abandoned their fellow Jews; if they protested, they ran the risk of seeming to confirm Hitler's delusions about the power of Jews around the world.

[Men chanting in German] Narrator: Rabbi Wise hoped that President Roosevelt could be persuaded to issue a formal rebuke of the Nazi regime.

FDR loathed Hitler, whose "Mein Kampf" he had read in the original German, and whom he privately called "a madman."

He and Eleanor Roosevelt had both been brought up in a rarified patrician world in which antisemitism was commonplace.

But life in the multi-ethnic world of New York politics had altered their perspective.

FDR was seen as a friend by American Jews.

Lipstadt: He knew a lot of Jews and he's close, he's a neighbor of Morgenthau, who will go on to be secretary of the treasury.

[Cheering and applause] But he wants to be very careful.

He knows he has a horrific financial situation facing the United States.

[Crowd cheering] Narrator: In 1932, FDR had been the first major party candidate ever publicly to denounce prejudice against Jews and had been rewarded with between 70% and 80% of the Jewish-American vote.

The federal government had always been the private preserve of white Anglo-Saxon Protestants.

FDR opened it up to men and women of talent, regardless of their faith.

He appointed more Jews to his administration than any president before him.

But much of their counsel continued to be divided, and most of those closest to Roosevelt warned that speaking out would only further endanger Jews in Germany-- and intensify antisemitism at home.

Lipstadt: If anything, they pulled him back.

Don't get involved, don't make a statement, you'll only make it worse.

Narrator: Roosevelt would for now side with those who urged caution, hoping that conciliatory gestures to Hitler on other fronts might encourage moderation.

[Children shouting indistinctly] [Man speaking German] Stern: It was a gradual process.

[Man speaking German] First, there were some kids who didn't greet you anymore.

But it was so gradual that you accepted, or not accepted, but tried to ignore these early manifestations of a change of ideology into evil.

Man: Everything was fine until, I don't know, I was maybe 3 or 4.

One of the kids that I played with called me a dirty Jew and beat me up.

So, after that, I stopped going to play in the courtyard.

Narrator: Sol Messinger's parents, like thousands of other Polish Jews, had emigrated to Germany, hoping to escape poverty and antisemitism.

They settled in Berlin, which had been one of the most tolerant cities in Europe.

Messinger: Across the street from us, on the ground floor, there were many shops.

About half of them were Jewish owned.

And I remember one day, I saw crowds of people forming.

And eventually somebody threw a rock through the window, broke the windows.

And the people went into the stores and simply took the merchandise.

There were policemen standing there, and they did absolutely nothing.

They just allowed it to happen.

Narrator: Susan and Joseph Hilsenrath lived with their parents and little brother in western Germany.

Susan Hilsenrath: I was born in a small town in Germany, in Bad Kreuznach.

Our life was pretty good.

My father had a linen store.

And we--he was doing really well and taking good care of his family.

We were very happy living in our house until Hitler came into power.

They boycotted my father's store.

He wasn't able to make a living for us anymore.

Joseph Hilsenrath: With the rise of the Nazis, of course, he had to close his business.

And he peddled fruits and vegetables as-- to--just to make a living.

And, but he managed, somehow.

I'm flabbergasted when I think about it.

We moved to an apartment, and then another apartment.

So, it was--each step was a down step.

And it was always because we were Jewish, we had to move.

Susan Hilsenrath: My parents did want us to have a normal childhood in an impossible situation.

I mean, we couldn't help but see.

I mean, we were intelligent children.

But we didn't understand, really, that it was going to get any worse.

And I guess maybe a lot of Jews that were living in Germany at the time didn't know that it was going to get worse, but it did.

Narrator: On the evening of May 10, 1933, students in Berlin and some 30 other university towns raided their campus libraries, carried out armloads of books by Jewish authors and by those Gentile writers deemed by the Nazis to embody an un-German spirit, and flung them into bonfires.

Writings by Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann and Ernest Hemingway and Rosa Luxemburg and scores of others all went up in flames.

The book-burning marked the end of a month during which the Reich had promulgated its first openly anti-Jewish laws.

With certain exceptions, men and women of so-called non-Aryan ancestry were ordered to leave government service.

Jewish doctors and dentists were barred from treating patients enrolled in the government health system.

Jews were no longer permitted to enter the legal profession.

Jewish editors and journalists, artists, and musicians lost their livelihoods.

Joseph Goebbels, Hitler's Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, presided over the book-burning in Berlin.

He exulted that it marked the end of Jewish intellectualism.

Lipstadt: It's step by step.

Jewish judges are fired.

Jewish lawyers who work in the courts are fired.

Jewish teachers are fired.

The Nazis were very attuned to what the public reaction would be.

It was drip, drip, drip.

They're judging.

They're very careful of what the German people will accept.

Narrator: Hitler eliminated opposition parties, crushed the labor unions, and would eventually order the murder of potential rivals.

[Hitler speaking German] Narrator: The goal of the Nazi government, Goebbels said, was that "there should be only one opinion, one party, and one faith in Germany."

Woman: There are to be no minorities of opinion in the new Germany and no division of loyalties.

Most men will wear uniforms, the badge of their membership in that secret, mystic community of blood-brothers, the German state.

Women will, by preference, wear kitchen aprons and will stay home and take care of the children, which they will gladly bear in large numbers for Germany.

They will not hold political opinions, but then, neither will anyone else.

Dorothy Thompson.

"Saturday Evening Post."

Narrator: It was not easy for foreign correspondents to report what was really happening in Germany.

Sources were often too frightened to talk.

Reporters were reluctant to quote witnesses by name for fear of betraying them to the secret police, called the Gestapo.

The Nazis controlled the German press and exhorted foreigners to "report on affairs in Germany without attempting to interpret them."

What that meant, the American journalist William L. Shirer wrote in his diary, "is that we should jump on the bandwagon of Nazi propaganda."

But the best American journalists did write about what was going on, however much the Nazi government tried to hide it.

Edgar Ansel Mowrer of the "Chicago Daily News" covered Hitler's rise to power with such brutal candor that in the summer of 1933, the Nazis made it clear they could no longer guarantee his safety in Berlin.

As Mowrer was leaving the country, a Nazi official asked when he thought he might return to Germany.

The American answered, "When I come back with about two million of my countrymen."

Dorothy Thompson's turn would come the following summer.

She had covered Europe off and on since 1920, earning a reputation for vivid reporting and for making herself part of her stories.

She had interviewed Hitler for "Cosmopolitan" magazine before he came to power and had dismissed him then as "formless, faceless, insecure, the very prototype of the little man."

But she had also read "Mein Kampf," saw that Hitler's nightmare vision of Germany's future was fast becoming a reality, and refused to mince words while saying so.

"The situation for the Jews is just ghastly, helpless," she said.

"Not only are the reports about the atrocities unexaggerated, they are underrated."

She returned to America for a time, but continued to write for the "Jewish Daily Bulletin" in New York.

When she visited Germany again in the summer of 1934, Hitler, who had never forgotten her scornful article about him and was appalled that she, a non-Jew, had written for a Jewish publication, personally ordered her out of the country within 24 hours.

On the morning of August 26th, she boarded a train for France, her arms filled with American Beauty roses given her by her admiring colleagues.

"I really was put out of Germany for the crime of blasphemy," she commented.

"My offense was to think that Hitler is just an ordinary man."

Thompson: There seems to me to be a certain misunderstanding about the Hitler movement.

A great many people seem to think that the persecution of the Jews, which has followed the accession to power of Hitler, is the result of something that they have done.

As a matter of fact, antisemitism has been a plank in the National Socialist platform for 13 years.

So-called civilized people didn't believe that if they came to power, they would carry this program out.

Narrator: Thompson's expulsion made her an instant celebrity in the United States.

She undertook a 30-city lecture tour, warning that, "Germany has gone to war already and the rest of the world does not believe it."

And in a syndicated column, she called upon Washington again and again to ease the barriers that kept desperate German Jews from emigrating to the United States.

But the State Department claimed that very few actually wanted to come to America.

Erbelding: In the 1930s and 1940s, you could be openly antisemitic and serve as a State Department official.

The rest of Washington is changing.

They're changing under the Roosevelt Administration.

They're changing with the New Deal.

But State Department officials were more conservative, they were more antisemitic, they were more nativist, at least openly, than anywhere else in Washington.

Narrator: Consular officials in Berlin and everywhere else in Europe continued zealously to enforce the old directive to deny a visa to any would-be immigrant "likely to become a public charge," and therefore required extensive data on each applicant's financial resources.

Lipstadt: The American diplomat at certain consulates giving out visas would have to essentially engage in divination.

Is this person likely to become a public charge?

Well, they say they have an uncle who will support them, we have all these letters, but an uncle is not a parent, it's not a sibling.

You couldn't come if you already had a job, because that meant you were taking a job away from America.

You couldn't come if you didn't have a job, because it meant you might end up on the dole or have to get government support.

Narrator: They also continued to insist upon duplicate copies of birth certificates and government documents attesting to an applicant's good character.

"It seems quite preposterous," one man recalled, "to have to go to your enemy and ask for a character reference."

Having made it nearly impossible for Jewish Germans to obtain visas, the State Department then cited the lack of applicants to reassure the White House that there was no immigration crisis.

Congressman Emanuel Celler accused the consular service of having "a heartbeat muffled in protocol."

Frances Perkins, Roosevelt's Secretary of Labor, sided with critics of the State Department.

The first woman ever to serve in a presidential cabinet, she had known and worked with immigrants all her life, believed the United States should be a haven for refugees, and promoted a plan to make their entry easier.

But the State Department refused to relax its rules.

"If ships begin to arrive in New York City laden with Jewish immigrants," one consular official wrote, "the predominant Gentile population of the country "will claim they have been betrayed through a sleeping State Department."

Public opinion overwhelmingly opposed loosening restrictions.

Lipstadt: People were out of jobs.

People were standing on food lines.

"You're going to ask me to worry about the persecution "of 600,000 or 585,000 Jews in Germany?

I can't feed my family."

Narrator: And Roosevelt's willingness to work alongside Jews had already become a source of controversy.

Right-wing orators now denounced what they called the Jew Deal.

Others claimed FDR himself was a Jew whose real name was Rosenfeld.

Antisemitic organizations proliferated across the United States, more than 100 of them before the decade's end.

On the East Coast, William Dudley Pelley, a mystic who believed he took his orders directly from Jesus, led a para-military fascist organization modeled after the Nazi Brownshirts called the Silver Legion of America and claimed there were 22 million Communists in the United States, all of them following orders from rabbis.

In the Midwest, an evangelist named Gerald Winrod assured his radio listeners that Roosevelt was a "devil" controlled by Jews, while Hitler was a "man's man" and a stalwart defender of Christianity.

A group that called itself the Friends of the New Germany desecrated synagogue walls with swastikas.

And Father Charles Coughlin, a Detroit priest with a radio audience of millions, blamed "Shylocks" and "international bankers," code words for Jews, for the Depression.

...would drive the money changers from the temple, and you did it.

[All cheering] Lipstadt: He begins to give overtly, unquestionably antisemitic sermons, many of which come straight out of Goebbels, many of which come straight out of German propaganda.

And millions of Americans tune in.

Narrator: A visitor to the White House reported that FDR was "quite apprehensive of the growing antisemitic and pro-Nazi sentiment in the United States."

[Whistle blows] Meanwhile in early 1935, Hitler revealed that he had begun to build an air force, the Luftwaffe, and called for a massive rearmament program-- artillery, submarines, an immense army, all of it in flagrant violation of the Versailles Treaty.

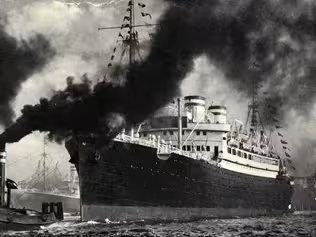

♪ On the night of July 26, 1935, the SS Bremen was preparing to set sail for Germany from Pier 86 in Manhattan.

She flew two flags-- the imperial German colors and at the bow, the crooked cross of the Nazi swastika.

1,300 passengers and elegantly-dressed friends had come aboard to see them off.

So had several thousand curiosity-seekers.

A dozen New York merchant seamen had also slipped aboard.

The American Communist Party Club on 10th Street had sent them to avenge a sailor who had been jailed in Hamburg for possessing anti-Nazi literature.

When it was time for guests to disembark, the seamen charged toward the bow.

New York cops and German crewmen tried to stop them.

One officer was badly beaten, one invader was shot in the thigh.

But two men managed to make it to the Nazi flag, and as onlookers cheered, they cut it loose and hurled it into the Hudson.

6 men were arrested and arraigned before a judge, a Russian immigrant named Louis Brodsky.

He jailed one protestor because he had worn brass knuckles.

But he let the others go.

The swastika, he said, was nothing but "a black flag of piracy."

It represented "a revolt against civilization, a merciless war against religion, against freedoms."

Nazi leaders eagerly exploited the incident.

An "impudent Jew in his bottomless hatred for Germany," Hermann Goering said, had insulted the whole country.

A formal protest was made to the State Department.

Secretary Hull said he would not question Judge Brodsky's decision, but he did express "regret" that the judge had indulged in "expressions offensive to another government with which we have official relations."

Hitler was not mollified.

At the annual Nazi party rally at Nuremberg in September, the swastika was declared the German national flag.

"It," Goering said, "has become for us a holy symbol.

It is the anti-Jewish symbol for the world."

At Nuremberg, the Nazis also issued a series of new and still more harsh antisemitic laws.

Jews, and potentially anyone opposed to the Reich, would become subjects, not citizens, of Germany, with no political rights at all.

To uphold the supposed racial purity of the German people, these laws banned marriage or sexual relations between Jews and persons of what they called "German or kindred blood."

The German jurists who wrote these laws had closely studied statutes in the United States that had for decades reduced African Americans to second-class citizens and barred interracial marriage in 30 states.

Greene: Even as the Nazis are writing the Nuremberg Laws that stripped Jews of their citizenship in 1935, they're looking to Jim Crow laws in the United States to understand segregation here.

Hayes: And when the Nazis were reproached for discrimination against Jews in Germany, their first answer was "Mississippi."

They were able to say, "In the United States, "you say that we should not treat these people "whom we regard as inferior badly, but you do it.

"You have lynching in the United States.

"You make it difficult for them to vote.

So how dare you reproach us for this?"

Erbelding: African-American newspapers at the time here in the U.S., they're saying, "You, the American people, "seem to be upset about what Hitler is doing.

"You're not looking down the street.

"We, too, are being persecuted.

"We, too, are being attacked by our own neighbors.

"Where are the marches for us?

"Where are the petitions for us?

Where are the rallies for us?"

Narrator: In one respect, the Nazi statutes were less harsh than many U.S. state laws that defined a person of color as anyone who had a single drop of Negro blood.

Instead, they categorized people as full Jews, Jews by definition, and mongrels of the first and second degrees.

Man: There has been no tragedy in modern times equal in its awful effects to the fight on the Jew in Germany.

It is an attack on civilization comparable only to such horrors as the Spanish Inquisition and the African slave trade.

Adolf Hitler hardly ever makes a speech today without belittling, blaming, or cursing Jews.

Every misfortune of the world is in whole or in part blamed on Jews.

There is a campaign of race prejudice which surpasses in vindictive cruelty and public insult anything I have ever seen, and I have seen much.

W.E.B.

DuBois.

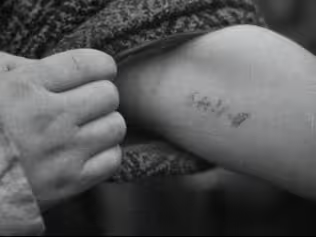

One night when my mother and I were out of town visiting my grandparents, a group of Brownshirts came and beat my father up.

We came back the next day.

And my mother took one look at him and screamed out, you know, "What have they done to you, Julius?"

It is a deep ingrained feeling that your parents are your protectors.

Now there is no protector.

Nobody is immune from persecution.

Hayes: In the 1930s, the objective of Nazi policy was to make life in Germany for Jews so miserable that they would leave.

And a fair number of German Jews understood right away.

There were 60,000 German Jews, more than 10% of the population, that left the country in 1933-'34.

They were fortunate in the fact that in the initial shock of discrimination against the Jews, of outrages against Jews, the neighboring countries, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Czechoslovakia, were relatively accepting of people who left.

And so, in that first wave of people, they got refuge in other countries.

As the 1930s went on, however, the willingness of these countries nearby to accept refugees declined.

And as more and more German Jews realized they needed to get out of the country, it became harder and harder for them to get out.

Man as Celler: To expect sportsmanship from the Nazis is impossible, for they obtained power by treachery, violence, and bloodshed.

To regard these men as true guardians of sports, to turn the Olympics games over to their administration is to invite the possibility that the Olympic games shall be befouled.

Emanuel Celler.

Narrator: In 1936, both the Winter and Summer Olympics were held in Germany.

Hitler saw an opportunity to show the world a reinvigorated, allegedly peace-loving country, its jobless rate slashed by public works programs and massive, rapid rearmament.

Some in Europe and America had threatened to boycott the Games because of the Nazi treatment of Jews.

But Avery Brundage, the president of the American Olympic Committee, who privately admired Hitler and personally disliked Jews, urged Americans not to be swept up in what he called a "Jew-Nazi altercation."

Congressman Celler denounced Brundage as the Nazis' "willing dupe."

On March 7, 1936, less than 3 weeks after the Winter Olympics, Hitler sent some 30,000 troops into the Rhineland, a German region that had provided a buffer between Germany and France, which according to the Treaty of Versailles was to remain demilitarized.

Thousands of German-speaking residents lined the roads to cheer them.

"The Führer is immensely happy," Joseph Goebbels noted in his diary that night.

"France won't take action, England remains passive, and America uninterested."

At the same time, Berlin was being transformed into a colossal stage set for the Summer Olympics.

Some 1,500 reporters were expected from all over the world, and the Nazi regime made sure that they would see only what it wanted seen.

They removed every sign forbidding Jews entry to restaurants, kept antisemitic publications off newsstands, and ordered newspapers not to report antisemitic incidents.

They also rounded up and interned several hundred Roma and Sinti people, often derogatorily referred to as gypsies.

"We must be more charming than the Parisians," Goebbels told Berliners, "more easy-going than the Viennese, "more cosmopolitan than the Londoners, and more practical than New Yorkers."

But anti-Nazi Germans managed to slip between the pages of a popular guidebook a map peppered with the locations of the scores of jails and prisons and concentration camps in which the regimes' enemies had been safely locked away.

Still, the Nazi genius for propaganda and pageantry overcame most visitors' doubts.

Man: The daily spectacle was breathtaking in its beauty and magnificence.

The stadium was a tournament of color that caught the throat, the massed splendor of the banners made the gaudy decorations of America's great parades, presidential inaugurations, and World's Fairs seem like shoddy carnivals in comparison.

Thomas Wolfe.

[Gunshot] Narrator: The Nazis were pleased when German athletes amassed the most medals.

But when Jesse Owens set 3 Olympic records and won 4 gold medals, they were appalled.

"That's a scandal," Goebbels wrote.

"White humanity should be ashamed."

In the future, Hitler assured his inner circle, the Olympics would always be held in Berlin and no "primitive men" would ever again be allowed to take part.

U.S.

Ambassador William Dodd had not been fooled by the Nazi pageantry and kept his distance from the Games.

Germany's Jews, he informed Washington, were anticipating the withdrawal of the world's attention "with fear and trembling."

Once the visitors had left, the Nazis resumed their indoctrination of the German people.

"We must bring up a new type of human being," Hitler had proclaimed.

"We have undertaken to give the Germans an education that begins with the child and ends with the old fighter."

His portrait hung in every school room.

Small children were made to recite poems in his praise.

Children's books were filled with venomous caricatures of Jews.

Millions of adolescents were made to join the Hitler Youth.

Parents of children who refused to join were investigated, fired, sometimes imprisoned.

♪ Stern: My mother had a good insight.

She said, "This will get worse and worse.

I will write to your Uncle Benno in America."

She wrote and said, "Can you save us?"

Back came the answer.

He said, "You know, I have lost my job "as a baker and pastry maker, "and so I can take one of you, but not all of you."

Behind my back, a parental conference must have taken place.

And they said, "OK, we'll send the oldest," and with a mission of trying to find other Americans who could vouch for us.

Narrator: Günther was just 15 and ambivalent about leaving home.

Stern: There were countervailing thoughts.

One of them is that you were-- are going towards a terrific adventure.

And then this dismal feeling, everything I know would be forcefully torn apart.

Narrator: Günther finally agreed to go and to try to find someone in America with enough money to sponsor the rest of the family.

While his father began the laborious task of filling out the paperwork to obtain a visa for his son, he hired a local English teacher who had lived for a time in Brooklyn to teach Günther everything he could about America.

A few months later, Günther's parents again called the family together.

Stern: They took me once more in this good room, and there was papers all laid out.

It was the affidavit in concert with a American-Jewish Women's Organization.

They said, "You also have a date in about a month at the American consulate in Hamburg."

Narrator: Günther was filled with fear.

He knew that unsympathetic American officials in some cities, like the consul in Stuttgart, routinely turned applicants down over one technicality or another.

Stern: If you were confronted, like the one in Stuttgart, by a virulent antisemite, he followed the letter of the law beyond its intent.

That kind of news got around.

Narrator: Günther's appointment was with the consul in Hamburg, Malcolm C. Burke.

Stern: I was prepared to be grilled.

He started out, you know, very routinely.

"Where do you come from?

What's your parents like?"

And then, he said--I'll never forget that question-- "How much is 48 and 52?"

That was it.

He put his name on my Youth Identity papers.

And there I was, ready to immigrate.

Had we lived in Stuttgart, I was out.

Snyder: Almost all of the major rescuers were diplomats, people who seemed most of the time to have unglamorous lives, people who seemed most of the time to just be pushing one piece of paper from here to there.

But it turns out that one piece of paper, pushed from the right here to the right there, can save a life.

Narrator: In the fall of 1937, the date of Günther's departure was set.

Stern: It was a highly charged, emotional couple of weeks.

My mother had taken me on very long walks through the city in the few days we still had together.

I had played games against my brother Werner, and he against me.

And all that was going to be taken away.

♪ Narrator: In November, Günther Stern arrived in New York City aboard a German ship.

After the German Jewish Children's Aid Society determined his English was good enough for him to travel alone, he boarded a train and headed for St. Louis, where his aunt and uncle were waiting for him.

5 days after he got there, Günther was attending high school.

He got his first job washing dishes at a downtown hotel.

But the plight of his family back in Germany and the responsibility he felt for finding a way to bring them to America, too, never left him for long.

[Film projector whirs] In the summer of 1937, Herman and Lotte Bland of Chicago, who had come to America from Poland, took their two sons to see the country where they had been born.

Leonard, their oldest, carried a brand-new 16-milimeter camera.

Harold, who turned 8 on the trip, was deeply affected by the poverty and the antisemitism he saw there.

In Suwalki, they met Lotte's cousins, and she installed a new headstone on her parents' grave.

In the town's central square, Leonard noticed that someone had scratched "Kill the Jews" in wet cement, and he captured it on film.

Minutes later, Polish policemen arrived and detained the whole family.

Officers tore the film from Leonard's camera, and after several tense hours, finally allowed the frightened Blands to leave.

In the years to come, nearly all of Suwalki's 14,000 Jewish inhabitants would be murdered.

Even the Jewish cemetery would be destroyed, as if the generations buried there had never existed.

[Airplanes whirring] In 1937, the world's authoritarian regimes were entering a new, more threatening phase of conquest.

Hitler had taken back the Rhineland.

Benito Mussolini's Italian fascist troops had crushed Libya and invaded Ethiopia, dropping bombs and deploying mustard gas against helpless civilians.

Japanese forces invaded China.

In Spain, German and Italian warplanes conducted terror bombing raids in support of a fascist uprising against a duly elected left-wing government supported by the Soviet Union.

Neither France nor England nor the United States was willing to intervene.

Franklin Roosevelt had been re-elected by a landslide in 1936.

4 years of the New Deal had helped restore American confidence and begun to put the country back to work.

But Roosevelt was an internationalist presiding over an isolationist country.

Senate hearings had convinced millions of Americans that Wall Street bankers, munitions makers, and British propagandists had conspired to trick the United States into entering the Great War.

Gerald Nye: American commercial interest is selfish and greedy.

Sensing the opportunity for profit from war would do as they have done in the past if left to pursue their own course.

Narrator: 125,000 college students had staged a one-hour Strike for Peace, and 60,000 of them signed a pledge never "to support the United States in any war it may conduct."

Congress had shrunk the Army, kept the country out of international organizations, and passed two Neutrality Acts, barring the sale of arms or war materiel to any belligerent anywhere.

In Chicago, President Roosevelt publicly expressed his alarm.

Roosevelt: The epidemic of world lawlessness is spreading.

And mark this well, when an epidemic of physical disease starts to spread, the community approves and joins in a quarantine of the patients in order to protect the health of the community against the spread of the disease.

[Applause] Narrator: Outraged pacifists now charged that Roosevelt was starting America down the slope to war by calling for a quarantine.

Isolationist congressmen threatened to impeach him.

The leaders of his own party remained silent.

"It is a terrible thing," he told an aide, "to look over your shoulder when you are trying to lead and find no one there."

Erbelding: There is no real perception in the 1930s that America is a force for good in the world, or that we should be involved in the world at all.

There is no sense among the American people, among the American government, among the international community, that it's anyone else's business what is happening within, you know, your own country.

It is not illegal what Hitler is doing to the Jews under International Law.

You can attack your own citizens under International Law at this point.

Narrator: American corporations, like those of other countries, continued to conduct business as usual with the Hitler regime.

The Nazis awarded Henry Ford their highest civilian medal, and his German plant began supplying the German army with 1,500 vehicles a year, after turning down an offer to build airplane engines for Britain.

Woolworth's German subsidiary fired all its Jewish employees as the price of doing business.

So did the Berlin office of the Associated Press.

All but one of the major Hollywood studios went along with the Nazis, too, even though many of the men who ran them were Jewish.

Joseph Goebbels had closed the lucrative German market to any film "considered detrimental to German prestige."

For a time, the German vice-consul in Los Angeles had the power to approve or disapprove scripts before production began.

Between 1933 and 1939, not a single word was uttered against the Nazis on screen.

The 80 million Americans who went to the movies each week got brief glimpses of Nazi Germany from newsreels made by Pathé, Paramount, Fox Movietone, and Hearst Metrotone News.

But the footage was usually confined to film produced by the Nazis.

Film announcer: In united Germany is the rallying cry of Chancellor Hitler as he tours the country.

In Westphalia, he is greeted by a tremendous throng of enthusiastic admirers.

[All cheering] Narrator: "The March of Time," a series of shorts made in association with "Time" magazine, was different.

In January of 1938, it offered a film called "Inside Nazi Germany" that included scenes shot by American cameramen when Nazi minders were not looking.

Film announcer: Still going on as pitilessly, as brutally as it did 5 years ago is Goebbels' persecution of the Jews.

Sign-posts at city limits bear the legend, "Jews not wanted.

Jews keep out."

Nazi Germany faces her destiny with one of the greatest war machines in history.

And the inevitable destiny of the great war machines of the past has been to destroy the peace of the world, its people, and the governments of their time.

Woman: The Nazis wanted to annex Austria, and there was supposed to be a voting if Austria wanted it.

Hitler didn't wait for a vote, just marched in in March 1938.